A Tribute to the Memory of Mr. Ryojiro Furusawa : HIROKI Koichi [Translaition : Sumi Matsuyama]

Mr. Ryojiro Furusawa was born on September 5th, 1944 in Sendai, in the Tohoku region of Japan. After World War II, Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, led by the United States. Sendai was also under occupation of the United States Army for an extended period of time because there had been a major Japanese military base there. “Give Me Chocolate!” used to be a common phrase for children of those days to pester the soldiers for a chocolate. Mr. Furusawa was one of these children. It must have been a humiliating experience for him. Given the circumstances, he must have gone through various hardships in his boyhood. Meanwhile, he had the good fortune to have contact with foreign cultures. During his high school days, he was crazy about a radio program, “Torys Jazz Game.” He lived in Sendai until he was 18 years old. Afterward, he moved to Nishi-Ogikubo in Tokyo and spent the rest of his life there.

Full of Curiosity

“Nande?” (Why?) was his favorite word and a way of expressing his endless curiosity. He often said “Nande?” with a Tohoku accent. His “Nande?” had his original intonation. He never accepted an ambiguous reply for it. He always pursued the “reason” up to the hilt. For this reason, it required mental and physical toughness to converse with Mr. Furusawa. He never stopped the discussion until he left. In musical performance, he always made a large-minded and affectionate reaction even when I played an immature phrase. There was a clue for the next phrase and conversation in his reaction.

The Greatest Reggae of Mr. Furusawa

In the late 1970s, one of the most common types of jazz was under the influence of John Coltran’s style. The feature of Coltrane’s style was to develop music from a small piece of motif. Mr. Furusawa had expanded his interest into Latin America’s rhythms and various rhythms of other ethnic groups as well as swing and other African-oriented rhythms. Above all, “reggae,” which is characterized by its bouncy beat and inflective sound, attracted him. Mr. Furusawa found a large and distinctive space, and the band filled the space successfully. He was looking for a guitarist and the late Mr. Motonobu Oode was selected.

It was at this moment that the “Furusawa Ryojiro Quintet” was launched. It was developed from the former “Furusawa Ryojiro Quartet.” Mr. Furusawa first met Mr. Oode in the street, by accident, and recruited him without an audition, simply saying, “Let’s play together in my band!” Their relationship began on a great gut feeling between them. After a while, Mr. Oode seceded from the band, due to scheduling problems, and I joined the band in his place.

At first, as a young new guitarist, I preferred jazz and was embarrassed to play the simple pattern of reggae, “mm-cha, mm-cha”. However, Mr. Furusawa’s futuristic aim was beyond our imagination. He predicted the effect and power of the sound when the guitar and the high-hat or the bass drum and the bass guitar wrapped over it.

Soon, the “Furusawa Ryojiro Quintet” was renamed as the “Ryojiro Band.” There were always two keyboard players and two or three guitar players in the “Ryojiro Band.” Excellent ideas and strong musical skills are required when multiple players on the same instrument play together. This is especially true for the rhythm part. We practiced a lot to avoid overlap in the same instruments and divided each person’s responsibility.

Mr. Furusawa often instructed me saying, “Kire!(chop!)” in a loud voice. Such instruction made me aware that I had been doing unsteady and loose comping. Mr. Furusawa requested that at least one combination of pianist and guitarist should do rhythm comping simultaneously. Generally, classical music put a premium on one’s sense of color and tonal combination. Mr. Furusawa’s experiences in classical music in his early days might have affected his sounds. At last, the “Ryojiro Band” succeeded in performing unprecedented sounds with unequivocal ambiance. The result was broad, rich and warm: Mr. Furusawa’s reggae.

Two Bass Players

Mr. Furusawa played with two excellent bassists, Guzura San (Mr. Hideaki Mochizuki) and Bata San (Mr. Tamio Kawabata) from the start of his career. He never expressed any anxiety about the bassists. People might be familiar with how happy of a drummer he was; no other drummers could achieve it. He often mentioned the two bassists in a confident and cheerful voice. The contrabass performance of Guzura San at “Furusawa Quartet” and “Furusawa Quintet” was always simple and supported the band from the bottom of the sound. In this way, Mr. Furusawa could play his drum freely without hesitation. In the “Ryojiro Band,” Bata San played electric bass. It was challenging work to build up the foundation of such a large band—8 to 10 players. The rhythms made by the combination of drums and bass played an important role in Mr. Furusawa’s music. However, while “Ryojiro Band” progressed satisfactorily, Mr. Furusawa was in anguish over people’s expectations and his heavy responsibility. Furthermore, the demise of younger Bata San left a gaping hole in his heart.

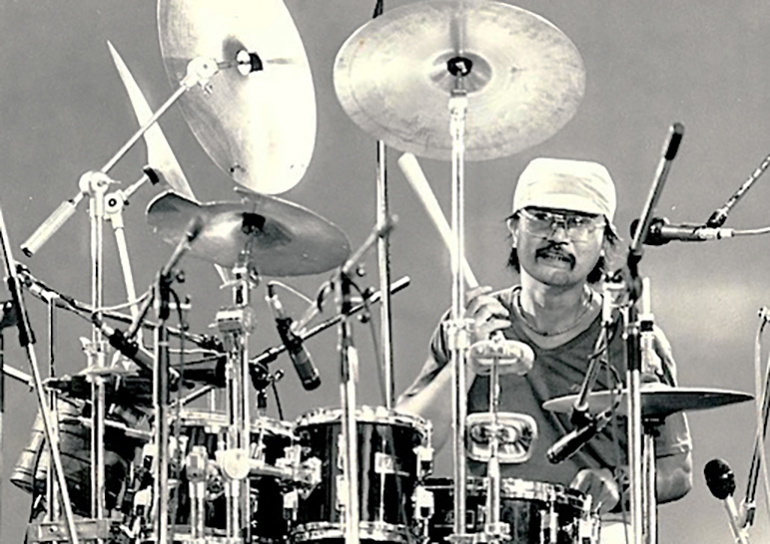

The General of a Vast Army

Mr. Furusawa in “Ryojiro Band” was like the general of a vast army. He could play relatively longer drum fills that were more than two bars (or four bars). He could play long snare drum rolls until the scene of the music would change by using various ways of expression. His drum fills were fingerposts for the next movement and direction. His long, sustained and clear-cut fills at the most appropriate time were like a word of command which could advance a great number of soldiers. He often told his students, “Start with fills!” He taught that a drummer should not start their play out of the blue. This lesson could apply to all other instruments. He expected his students to play decisively and cautiously while predicting the outcome, as a drummer’s play always has a significant impact on the music. When you listen to the tune “Peak Wind” appearing in the album Tamaniwa (1983), worthy to be called a masterpiece, you will notice that he sometimes omits the snare drum at the 4th beat intentionally. How sophisticated he was! The aesthetic of elliptical expression comes into effect only when the minimum requirements for the music exist. Mr. Furusawa’s performances went beyond the listener’s expectations.

Mr. Furusawa As a Composer

I hope Japanese music school textbooks adopt the compositions of Mr. Furusawa. Also, many fans expect his music to be extensively disseminated via the media. He used to compose music during his promenade. He could grasp the small variations of day-to-day situations and bring them into his compositions. He could compose a piece of music in no time without playing any instruments. Everyone can hum his compositions easily because all of his tunes are in accordance with the rhythms of the Japanese language.

Mr. Furusawa studied classical music in college (he was also a good pianist). He was fascinated with Jazz and sought to explore various kinds of ethnic music after graduation. Then, he went back to a Japanese-oriented rhythms. The sources of his ideas existed in Japanese elements and language. In other words, he described the everyday things in a very natural way by the taste of the native tongue after digesting all kinds of music and rhythms from across the world. His originial and visceral messages penetrated the minds of people worldwide.

He sometimes composed music while having a vision of the ensemble of his band. Sometimes he dedicated his music to his family or friends. He always had good intentions and motivation, and he always kept curiosity alive and had his heart and soul in mind. He often said simply, “Love! Love!” The rhythmic patterns were either well-designed or improvised case by case. The rhythm section solidified the foundation of his music. He played his own works, which means that his music had strong powers of persuasion. He himself did not play the melody or chords. And while he did not sing a melody, I felt as if he had. He had the ability to concretize his music well despite the fact that he was just hitting drums, which meant he was in a position of inspiring other members rather than playing the melody by himself. I believe his plans were very thoughtful and cautious. Mr. Furusawa offered ideas of melody (backbone) and rhythmic patterns (foundation) of the band, and the other members were encouraged to develop his ideas freely and colorfully while valuing their individuality. He was also good at bringing out a latent faculty. We usually conducted a short rehearsal of about 30 minutes just before going on stage. We roughly checked the sound because we put a premium on improvisation. Nevertheless, the arrangement was always completed just after Mr. Furusawa introduced a new composition.

The Supreme Chain

I used a phrase, “rhythmic pattern.” But this is not an appropriate expression for Mr. Furusawa. Usually, “rhythmic pattern” means a repetition of one or two measures, but he never played the same sound. He carried the music forward step by step, with his original rhythms. They were not fixed patterns. There were various nuances of note which was one of the most important elements of music. The content of thought on drumming was one of the most important matters to form the beat as well as musical factors like choice of instruments, tone, volume and speed. He performed while thinking simultaneously about what was needed now, how should he do it, how other members were thinking, what would be the result of the next shot and so on. He must have sharpened his senses, as a good improvised line yields a good comping, and vice versa. . It is like a chain of well designed, sophisticated and lively ad-libs. As a result, good rhythms and swingy beats were achieved. Running out of ideas or phrases could lead to the breakdown of rhythm. Rhythm cannot exist independently, but is a result of consecutive and quality conversations. The Supreme Chain was made by various factorial effects, such as the brilliant imaging of his composition, his attention to members’ performances both aurally and also visually and his peculiar gut feelings. Together, these created “Mr. Furusawa’s rhythm.”

Respect

I often hear the word “respect” come up in conversations with my friends in New York. In a multiethnic environment, it is necessary to respect each other. Mr. Furusawa grew up in the repressive environment of an occupied country. He must have experienced unreasonable things. During the postwar years of recovery, he had to develop his own ability to survive. He studied hard at a college of music in Tokyo and became a musician.

In the college, there was a strong boss-subordinate relationship in both coursework and also after-school activities. I became a member of the “Furusawa Ryojiro Quintet” at age 21. I was just a fledgling musician. Even still, Mr. Furusawa introduced me as an accomplished musician to other musicians, persons involved, clients and his friends wherever we went. He treated me as an equal partner to raise my awareness as a member of society, although I was just a cub with no experience or ability. Through this, I first understood the concept of “respect.” Mr. Furusawa was 32 years old at that time. Only 10 years had passed from his debut as a professional musician. But, he was already gentlemanly, logical and clear-headed. I learned that creativity could hold only when the people involved were respecting each other. I still have photographs of those days. I see myself in the photos as a weakly boy among hardened musicians. Maybe I belonged in the next generation of those days. I guess I sometimes bothered him. When my first concert with him was finished, he said to me, “Start with your best phrase!”

Powerful Music

His students often mimicked Mr. Furusawa saying, “Nandatte?” (Pardon?) They made fun of his heavy accent. He had lived for about 40 years in the town of Nishi-Ogikubo after he moved from Sendai at age 18; however, he never lost his Sendai accent. It is quite common for people from other provinces to accept the standard pronunciation of Tokyo, as the other people around influence them. But he did not. He was not clumsy. It was because he had an original sense of rhythm. In other words, he had a stubborn will about his native dialect. This original sense of rhythm yielded his powerful music. He was not influenced easily by other people. He did not have a fear of being different from other people, even living in the megalopolis, Tokyo. He was clever because he knew that the communication of ideas and significance was the first priority, rather than one’s fluency. He wanted to express many things. He wanted to play drums as much as possible. He created many melodies. He really enjoyed his performances. He was always curious about people. He was sensitive to the variations of the street. He loved cigarettes and Shochu. And he wanted to spend his whole life with his friends and colleagues. Now, Mr. Furusawa must be in the happy land of his hometown.